5G won’t reduce the digital divide and might even make it worse

By Peter Bloom

As laid out in my previous piece about 5G networks, much of the energy from the mobile sector around connecting the unconnected is dissipating. It is not that there are no efforts, for example the Telefonica/Facebook partnership in Peru, Internet para Todos, but simply that they are waning. This shift away from connecting people is important as the mobile industry has been seen over the past couple of decades as the magic bullet in terms of increasing connectivity. But with the focus on 5G, the number of those connected with mobile technology is unlikely to increase.

In this brief piece, I will place special emphasis on why 5G is poorly suited to close the digital divide and how it will, perhaps, widen it. The reason for this is simple: the mobile industry has engaged in substantial regulatory capture all over the world. In other words, they have managed to shape how telecommunications are regulated in ways that benefit their business and suite of technology. This happened because, frankly, they delivered. The mobile revolution was a real thing and millions and millions of people were connected to more affordable voice and data services. In response, regulators generally do the mobile industry’s bidding because mobile “works”. But that revolution is over. This is born out by the GSMA’s own numbers on slowing subscriber growth. The regulatory capture is important because the strength of the mobile lobby, and the regulations that have been shaped by it, are not conducive to allowing new entrants into the market (e.g. community networks) and potentially undermine other existing access technologies and providers (e.g. satellite).

From this analysis, it is probably time to find additional ways to solve the digital divide that are not only based on large-scale mobile if we really want to address getting half of the world’s population connected. The mobile industry is in the throes of a new revolution, just one that has little or nothing to do with increasing access or affordability. In fact it is not even clear when 5G will start rolling out at any scale. By the GSMA’s own estimation: “global 5G adoption will still only be around 16 per cent in 2025.”

A fundamental issue is that 5G is not human-centered. Communication between and among human beings is only a small part of the package, as is people accessing information and engaging in dialogue. As my previous piece highlighted, there is an important focus on facilitating machine-to-machine communications (“Internet of Things”) and converting 5G into a media distribution platform for HD television, gaming, virtual reality and the like. When people are no longer the intrinsic focus of the communication system, then something fundamental has changed about the nature and purpose of the network. 5G networks are being built to do something different and if we are concerned about how 3 to 4 billion people on the planet will be able to exercise their fundamental rights to communications and information, then we need to look elsewhere.

Not only is 5G problematic from a teleological standpoint, it is also unlikely to close the digital divide, and might even make it worse.

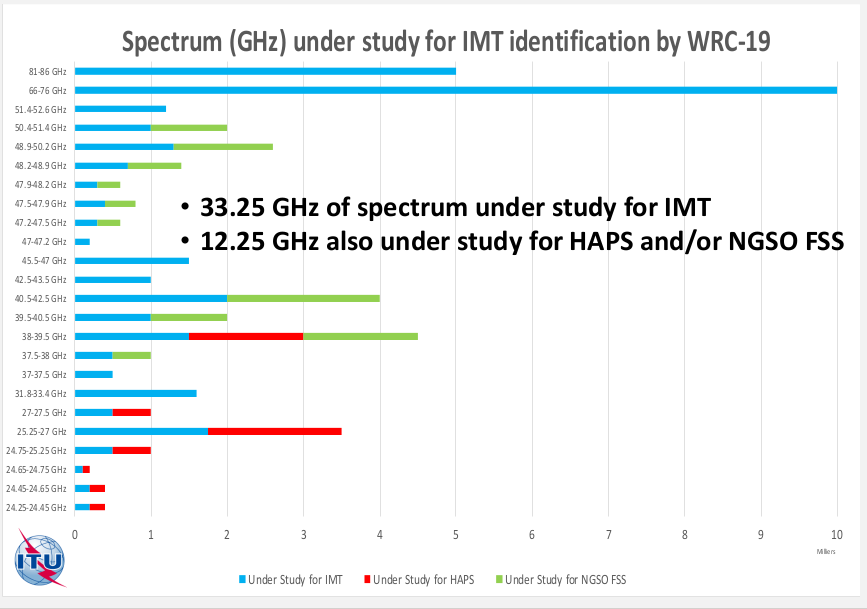

5G is incredibly expensive to deploy, even in optimal, urban conditions. The base stations are expensive, you need lots of them, and they require costly supporting infrastructure, like high-capacity fiber optic cabling, to operate. This makes sense if you want to create a very dense network to serve lots of data to lots of people in a small area. It does not make sense for rural areas, where generally you need to cover few people in a large area. As we know from our current situation, mobile networks struggle to operate sustainably in rural environments where population densities and available income are lower. This is why operators tend to avoid building anything in these kinds of places. If the major operators decide not to build out in new places, the fact that their spectrum licenses are generally national, means others cannot build the networks instead. Additionally, 5G, in most cases, requires operators to access new spectrum bands, which is not cheap. Mobile operators are investing lots of money to access millimeter-wave spectrum for 5G that is not feasible to use in rural areas as these very high frequencies are not well suited for covering large areas.

Since so much money is going into gaining access to spectrum and building these next-generation networks, it is possible that what little investment in rural areas currently happens, will actually decrease. And forget about prices dropping for existing services. The operators need money to roll out 5G and they are going to squeeze it out of existing users however they can. In places like South Africa, affordability of existing services is a major issue, even if there is coverage in most places.

Another way that 5G might make the digital divide worse is the ongoing fight between mobile operators and satellite operators for spectrum. There are disputes happening over the C-Band (4GHz to 8GHz), 28GHz and in higher V-bands (40GHz to 75GHz).  While satellite operators have struggled to make prices affordable, their technology is crucial for rural connectivity and has been for many years. In addition, the satellite industry is on the cusp of a major shift. High Throughput Satellites (HTS) and proposed low-orbit constellations should lead to dramatically increased capacity and lower prices for end users. If those technologies cannot access the spectrum they need, then they will have trouble growing and reaching people. In a later piece co-authored with my colleague Steve Song, we will look at some of these new technologies.

While satellite operators have struggled to make prices affordable, their technology is crucial for rural connectivity and has been for many years. In addition, the satellite industry is on the cusp of a major shift. High Throughput Satellites (HTS) and proposed low-orbit constellations should lead to dramatically increased capacity and lower prices for end users. If those technologies cannot access the spectrum they need, then they will have trouble growing and reaching people. In a later piece co-authored with my colleague Steve Song, we will look at some of these new technologies.

There is a final way that 5G could muck up the works and it has to do with drawing the attention of policy-makers and regulators away from ensuring affordable connectivity for all their constituents. Administrations around the world are setting up highfalutin commissions and sending their people all around the world to look into how their countries can embrace the 4th Industrial Revolution. This is all well and good, but it would be fantastic if such zeal and expertise went into dealing with present-day issues and not only those of the future. This argument is partially about regulatory capture, as noted above. It is also about the fact that in many countries with low connectivity penetration, communications ministries and telecoms regulatory agencies are understaffed, and there are only so many civil society, academics and independent people available to put energy into solving a problem. This shift in attention could also mean that government agency funding for research and development, as well as support to bridge the digital divide, might dry up for a problem that is nowhere near to being solved.

In summary, policy-makers and telecoms regulators have an important role to play in balancing the requirements of new 5G networks with their own stated goal of ensuring affordable connectivity for all. If they are committed to making spectrum available to mobile operators for 5G they must also find creative mechanisms to guarantee access to spectrum and backhaul for other connectivity models interested in bridging the digital divide, be it community networks or even satellite companies. Additionally, finance institutions and Universal Service Funds, especially those oriented towards poverty reduction and sustainability, should understand how their investments in 5G might leave room and money to pay for other, more appropriate technologies and business models, including community networks.